Going, going,

Gone.

Every Christmas since university, my bestie Laura and I exchange vinyls. Last year, I was lucky enough to receive Mitski’s latest, The Land Is Inhospitable And So Are We (2023) while I gifted Jim Sullivan’s UFO (1969).

A debut album inspired by Sullivan’s obsession with extra-terrestrial life, the LP received very limited praise at the time but has since become a bit of a cult classic. Part of this resurgence is because it sounds really flipping great. With a sound reminiscent of Eric Burdon and The Animals or John Prine, UFO was psychedelic, soulful and in parts very catchy. The other reason that the album has made such a triumphant return is that one day, six years after the release of UFO, Jim Sullivan disappeared and was never seen again.

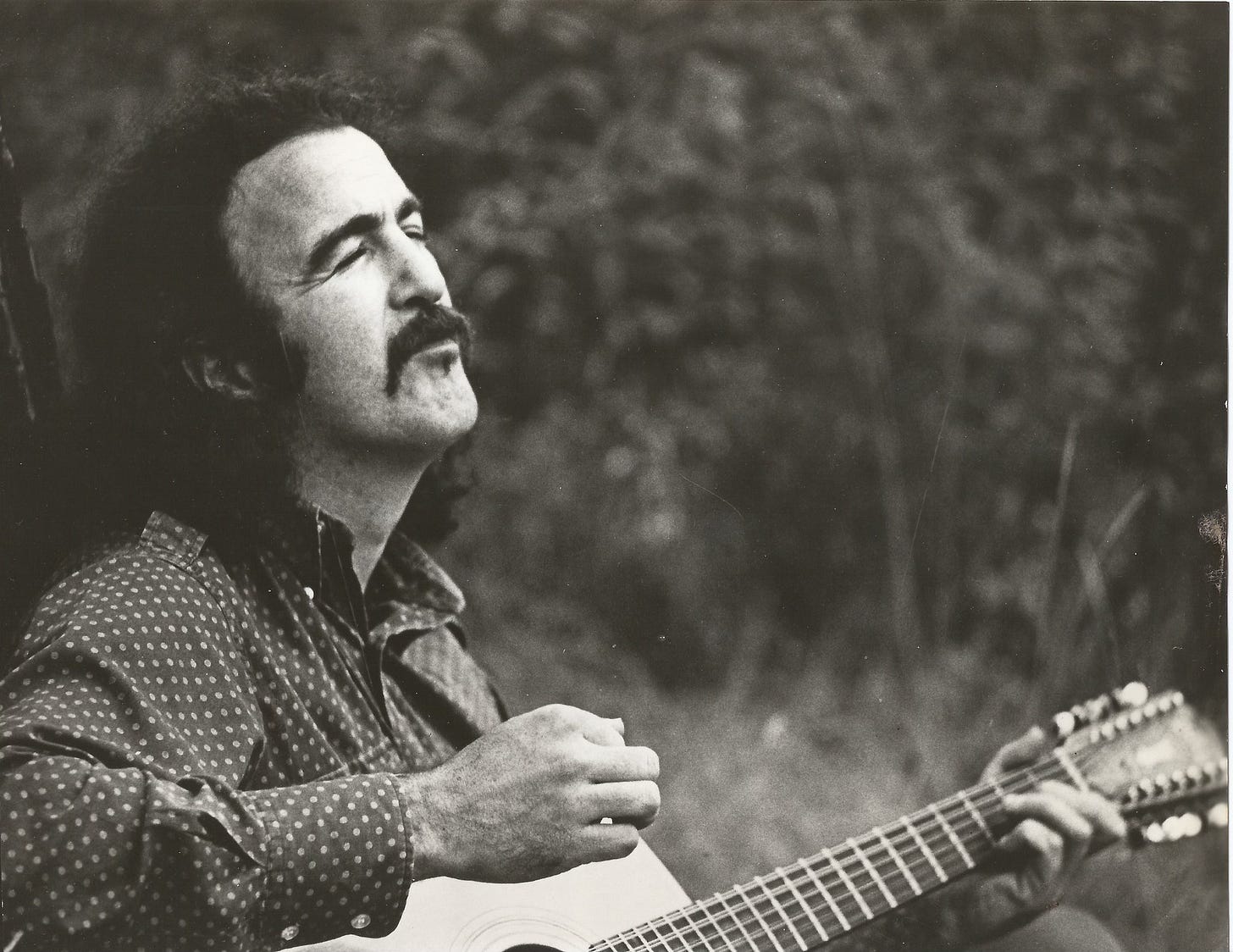

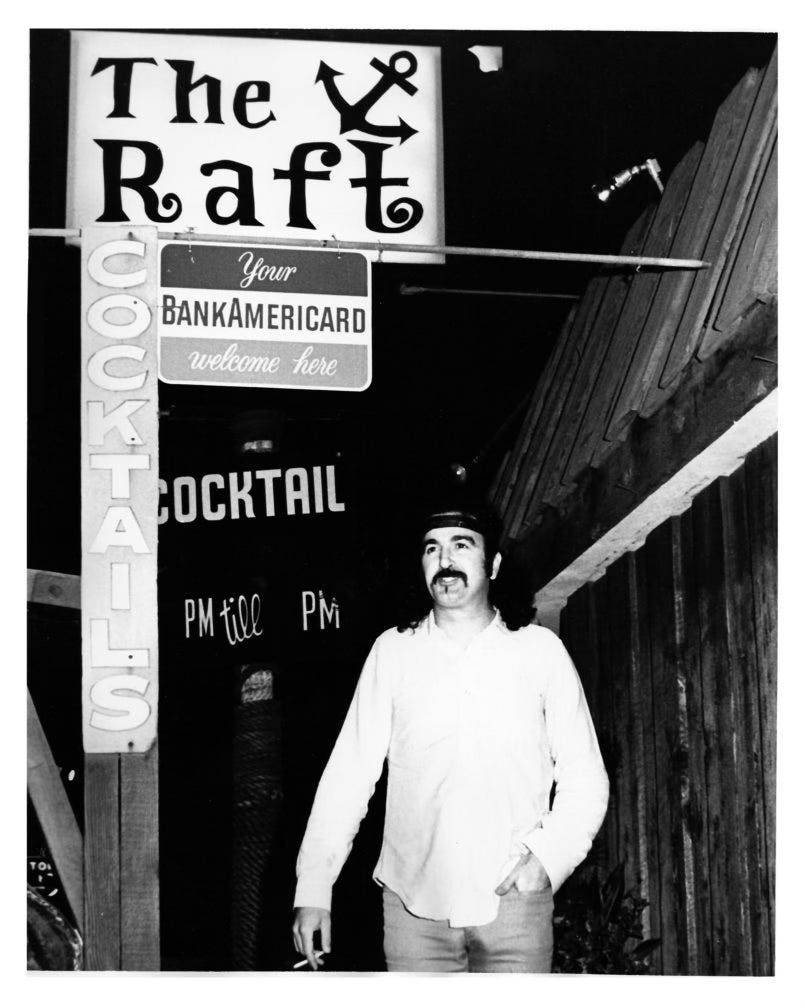

Jim Sullivan

Born in Nebraska in 1940, Jim Sullivan spent most of his childhood in San Diego, California, growing up to be a strapping young man, a tall quarterback who got the girl type shit. Someone who would’ve bullied Peter Parker essentially. He was confident, charming and passionate about his craft. One of the most frustrating parts of Sullivan’s story is that, anyone who met him or saw him perform thought he was truly unique. UFO was released by actor Al Hobbs, who literally formed a private label in order to press the album himself. When Playboy’s own Hugh Hefner decided to launch an ill-fated record label, Sullivan was one of the first acts scouted. Hefner associate Lee Burch visited Sullivan many times:

“I happened to come by a club where he was playing. He really impressed me. I went out to the car and got my guitar and sat in with him. I did that for several weeks, months, and we became friends.”

This magnetism earned Sullivan many fans from Hefner to Harry Dean Stanton to Dennis Hopper, but this proximity did not catapult his career to the extent it could have done. From earning a cameo in Hopper’s countercultural classic Easy Rider (1969) to recording sessions with legendary session bass player Jim Hughart and other members of The Wrecking Crew, he was well connected in Los Angeles. Even his wife Barbara Sullivan, an employee at Capitol Records would try unsuccessfully to land our Jim a record deal at a major label.

In his peak years, the frustration of having to do gigs every night combined with the inability to release new music and promote it effectively, likely had an impact on Sullivan’s confidence. With a wife and child at home, the nomadic aspect of regular, low-paid gigs may have put a strain on his ability to be present but also to “provide” in the 1960s nuclear family pater familias type sense. Sullivan’s career ended how it had begun, playing bars and clubs, hovering on the fringes of celebrity, mixing with those cool and hip enough to dig his groovy frequencies but never breaking through himself.

On March 4th, 1975, Jim Sullivan drove out of Los Angeles in his VW Beetle and headed towards Nashville, Tennessee on his own. He was reportedly stopped by a police officer who warned him about drink driving and ordered him to stop at a motel, which he apparently did. Leaving the motel relatively untouched, Sullivan drove further into the desert and was never seen again. When Sullivan’s car was later found at a ranch 26 miles from the motel, his belongings painted one final portrait of who the man was:

A stack of tapes, his self-titled Playboy LP, a guitar and an appointment book.

Now I’m not going to get true-crimey on this because that’s wack. You can come up with your own conclusions about what happened to Jim Sullivan, but his legacy is one of an under appreciated, overperforming body of work that felt truly unique and magical to listen to. Since being uncovered by Matt Sullivan, the owner of Seattle record label Light in the Attic, Sullivan’s music - UFO in particular - has reached an audience larger than Sullivan possibly imagined, an audience he richly deserved. Give it a listen while you read the rest of this letter, why not! Live a little!

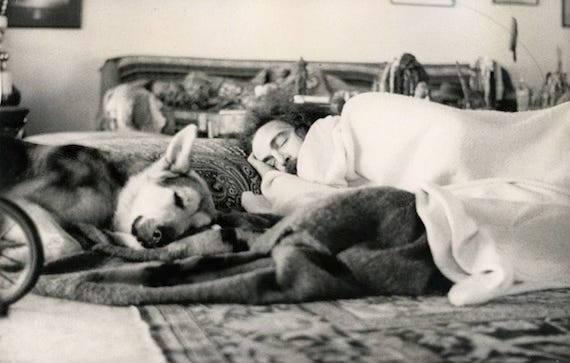

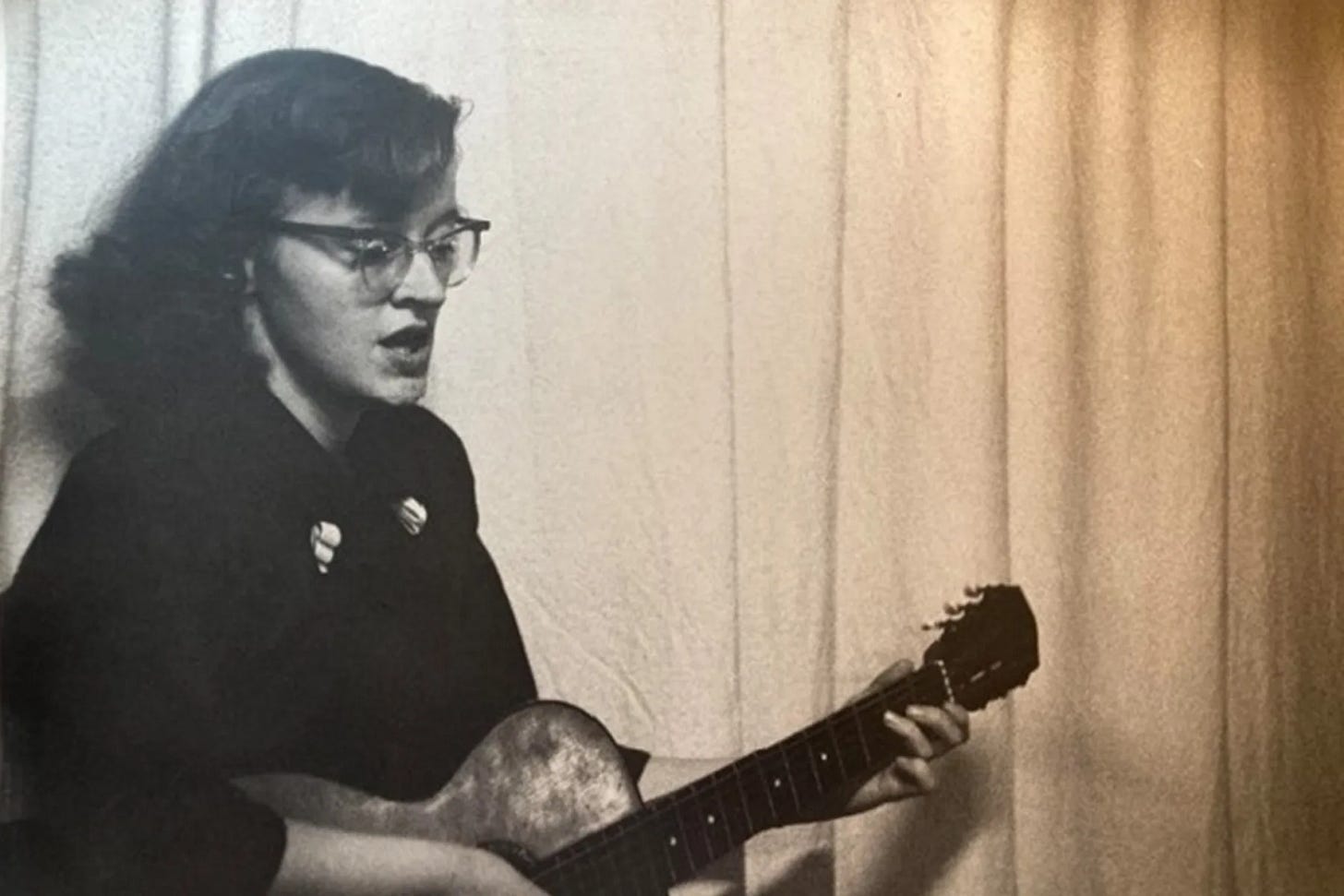

Connie Converse

See that brook running by my kitchen door; well it couldn't talk no more if it was you

Up that tree there's sort of a squirrel thing

Sounds just like we did when we were quarrelling

In the yard I keep a pig or two

They drop in for dinner like you used to do

I don't stand in the need of company with everything I see talking like you

Born one hundred August 3rd’s ago this year, Elizabeth Eaton Converse grew up in Concord, New Hampshire, USA, to an upright religious family with a fairly limited interest in creative endeavours. Elizabeth excelled at school before dropping out of a four year scholarship at Mount Holyoke College, the alma mater of multiple family members who were stunned at the time. Moving to New York City thereafter, Converse made tiny steps towards a music career, writing songs and performing mainly for friends under the nickname “Connie”. What limited publicity she received was driven mostly by those around her who appreciated her voice and writing talent.

Friends encouraged the singer to perform at a salon hosted by renown cartoonist and animator Gene Deitch, who recorded Converse. Impressed by the singer, Deitch managed to facilitate a brief appearance on The Morning Show with Walter Cronkite but again, this brief moment in the spotlight didn’t do much for Connie. The artist wasn’t especially interested in self-promotion and struggled to get into the right circles. Where Jim Sullivan was a charismatic performer who made friends wherever he went, Converse was a likeable yet very private person who shied away from the politics of fame.

What record we do have of Connie Converse’s discography is purely thanks to friends and family who recorded her and kept what recordings she made herself. In We Lived Alone: The Connie Converse Documentary, Connie’s nephew Tim recounts how one night while staying with her as a child, Connie played Tim some songs she’d recorded just as he was falling asleep. While it didn’t mean much to him at the time, it’s clear that his memory of the night decades later was shaped by her trust in him and an eagerness to share her music with people. It wasn’t that Connie didn’t want to be recognised, it was that she wanted it on her own terms.

After years of being at odds with who she wanted to be, Connie made a decision which ultimately shaped how she is perceived today. Just after her 50th birthday in 1974, Converse wrote a series of letters to friends and family, setting the stage for a new phase of her life. The letters suggested she was starting again in New York City and may be gone for a while. However in a letter titled “TO ANYONE WHO EVER ASKS: (If I'm Long Unheard From)” - an unsent letter left behind in her belongings - Converse wrote:

To survive it all, I expect I must drift back down through the other half of the twentieth twentieth, which I already know pretty well, to the hundredth twentieth, which I have only heard about. I might survive there quite a few years—who knows? But you understand I have to do it with no benign umbrella. Human society fascinates me & awes me & fills me with grief & joy; I just can't find my place to plug into it.

So let me go, please; and please accept my thanks for those happy times...I am in everyone's debt

While the other letters of departure made their way through the postal system, Converse packed her car and drove, never to be seen again. By the time anyone knew she wanted to go, she was already gone. And so was her music, for a while. It wasn’t until 2004 that Gene Deitch, the cartoonist who’d recorded her half a century prior, was invited onto a New York radio show with music historian David Garland. Showcasing a couple of her songs including “One by One” - the self-exiled musician’s work reached a much broader audience - some of whom were keen to seek out and restore Converse’s work before it was lost completely. Compiling Deitch’s own collection from his home in Prague and other works bestowed to her brother Phillip in Ann Arbor, Lau Derette Recordings members Dan Dzula and David Herman were able to release How Sad, How Lonely in 2009, a 17-track collection of Converse’s music.

Since then, Connie Converse has been recognised by music historians and fans alike as a singular discography from a unique voice, a folk singer-songwriter before singer-songwriters were a staple of the industry. Mixing overdubbed vocals - a pioneering feature of her music - to create haunting, romantic folk music with autobiographical storytelling, Converse is now remembered as a special part of folk history.

Bas Jan Ader

Content warning for: The Holocaust, brief mention of murder.

Bastiaan Johan Christiaan Ader was born in exceptionally tragic circumstances. His father, a Calvinist minister in the Dutch village of Drieborg, helped many Jews escape the horrors of the Holocaust during the Second World War, hiding them in his house and moving them across the country. When Bastiaan (hereby referred to as Bas Jan) was just two years old, his father was executed by the Nazis for his efforts, along with six other prisoners. His fathers’ conviction to his faith was unparalleled; asking his murderers to kill him last, so that he could support the other victims in their final moments.

By the time Bas Jan Ader was old enough to be aware of these events, the war was over and European society was keen to move on, to shrug off the shadow of conflict. Ader studied art in Amsterdam and then abroad in the US, eventually settling there and teaching at various instiutions while pursuing his own artistic practice. What strikes me most in his work, is the surrender of the body.

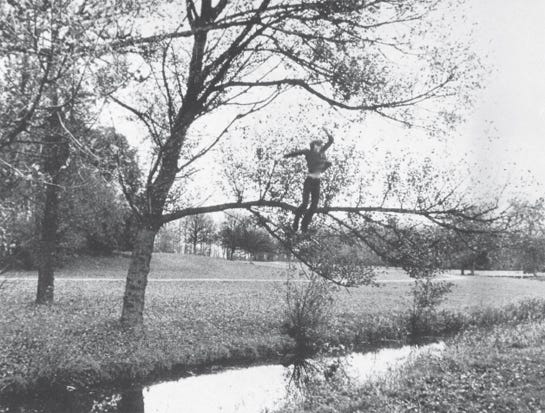

Broken Fall (Organic) from 1971 highlights something present in all of Ader’s best work (in my opinion) - a sense of inevitability, of surrender. This still from the work captures the moment the branch breaks, plunging Ader into the water below. The work is less about how or why Ader has climbed the tree, and more about the consequence. History is overwritten by the present. The drop is felt, not remembered, by the downward motion, an unpaid bill of damage.

Fall 2 achieves a similiar feeling - we know what is to come, the fall is what we feel not what we know or understand. The first in the series, Fall 1 from 1970 depicts Bas Jan falling from a chair on top of his roof into nearby bushes.

There is something cartoonish or Keaton-esque about these performances, almost slapstick in execution yet taken together with other projects highlight a sense of depersonalisation, a body subjected to an action.

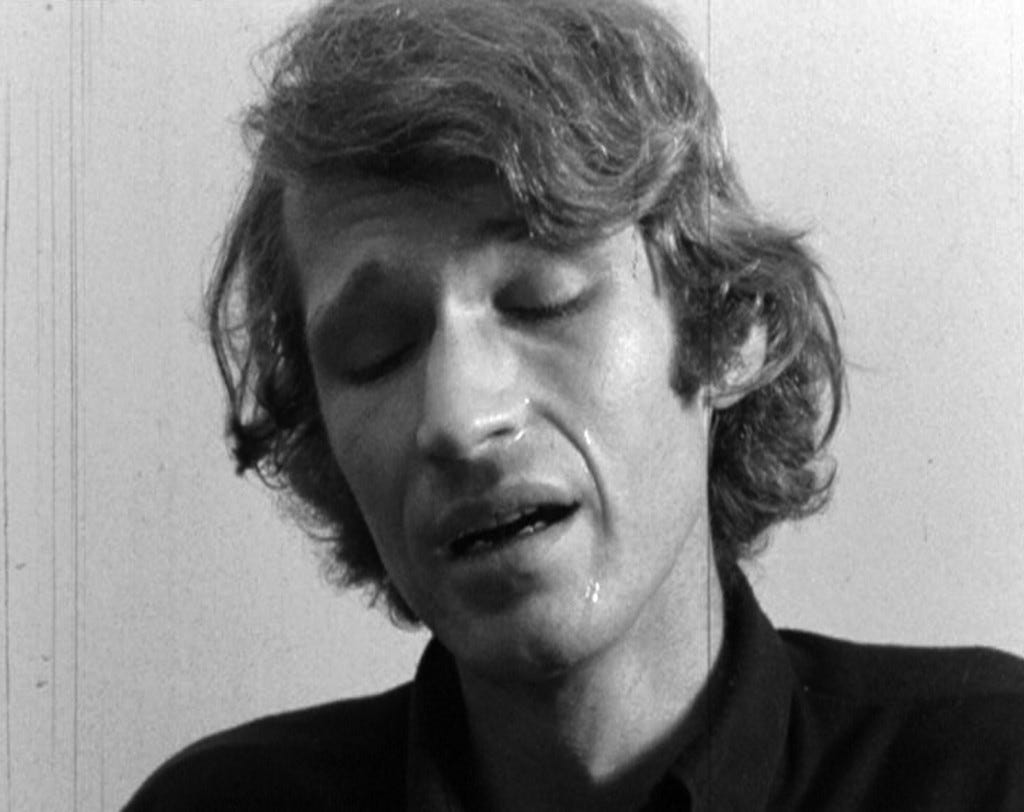

Perhaps his most iconic work, I’m too sad to tell you (1971), is a roughly 3 minute video of Ader crying, accompanied by photographs shared with friends. Again here the context is removed, dialogue is futile, it is too overwhelming a feeling to explain. His work is elusive in the sense it feels auto-biographical yet universal.

Ader’s final work, In search of the miraculous began in L.A. in 1973 with a series of photographs, a lone figure wandering the landscape with a torch. It ended with a voyage, one of humble proportions in the face of vast consequence. Traversing the Atlantic ocean in a boat just 12.5 feet long, Ader planned to sail in the smallest craft ever attempted. As bookends to the voyage, Ader arranged for sea shanties to be performed at the Claire Copley Gallery in LA before his departure and at the Groninger Museum in Holland upon his arrival, an odyssean return home. The second performance would not be realised, as Ader never arrived. A year after leaving America in 1975, Ader’s boat was found by a Spanish fishing vessel off the coast of Ireland, with no sign of the artist. His body was never found, the artist presumably lost to the abyss.

Whether intended as a magnum opus or a tragic accident, Ader’s disappearance symbolised the role his body had played in his work - as an object of inevitability, of gravity, of failure.

Rene Daalder’s documentary, Here is Always Somewhere Else, which sources Ader’s origins and the progression of his career in greater depth than I can provide here.

What is remarkable about Sullivan, Converse and Ader is the impact they had on their respective scenes despite the brief nature of their output. More than half of Ader’s work was made in the space of a few weeks. Sullivan released two albums, three years apart while Converse never released music to a wide audience, performing a handful of times in a public environment. Ader experienced recognition and renown whilst alive, however his ideas seem bolder and more realised in death, as though a final statement on what he pursued and sought to explain. Equally, Sullivan and Converse feel alive now more than ever, rediscovered and remastered in the internet age. As each artist fell away from public life, willingly or not, they left behind bodies of work that were brief, bright and brilliant.

I hope you enjoyed this letter! A dense one with a lot to digest, I hope I did it justice or at least sparked your interest in finding out more...feel free to let me know what you think here in the comments or at paulieratdepot@gmail.com

We have events coming up in September and October and I’ll be in touch soon with more info…until then, be good.

Love,

Paulie x

p.s - this email is “too long”, we have finally breached the void, we are in gmail limbo. If you’re reading this, it’s too late please save yourself.