Hi guys, long time no see (shocker, I know). I hope you’ve all been keeping well and are effectively hunkering down for the winter months, having many a pint and mince pie. This week I’m celebrating Palestinian art, art which stands defiant in the face of overwhelming, genocidal force. The news cycle is very bleak at the moment. Thousands of Palestinians, many of them just children, have had their lives taken by an unrelenting brutal regime who are backed by the geopolitical elites of the world including my own country, the United Kingdom. It is no surprise that a country as spiritually bankrupt as my own has no qualms offering arms and military support to a genocidal project, but it is still sickening and deeply shameful.

If this space is good for anything at all, hopefully it is capable of spreading a little bit of joy in your inbox. So here’s three Palestinian artists that have made beautiful art for you to enjoy.

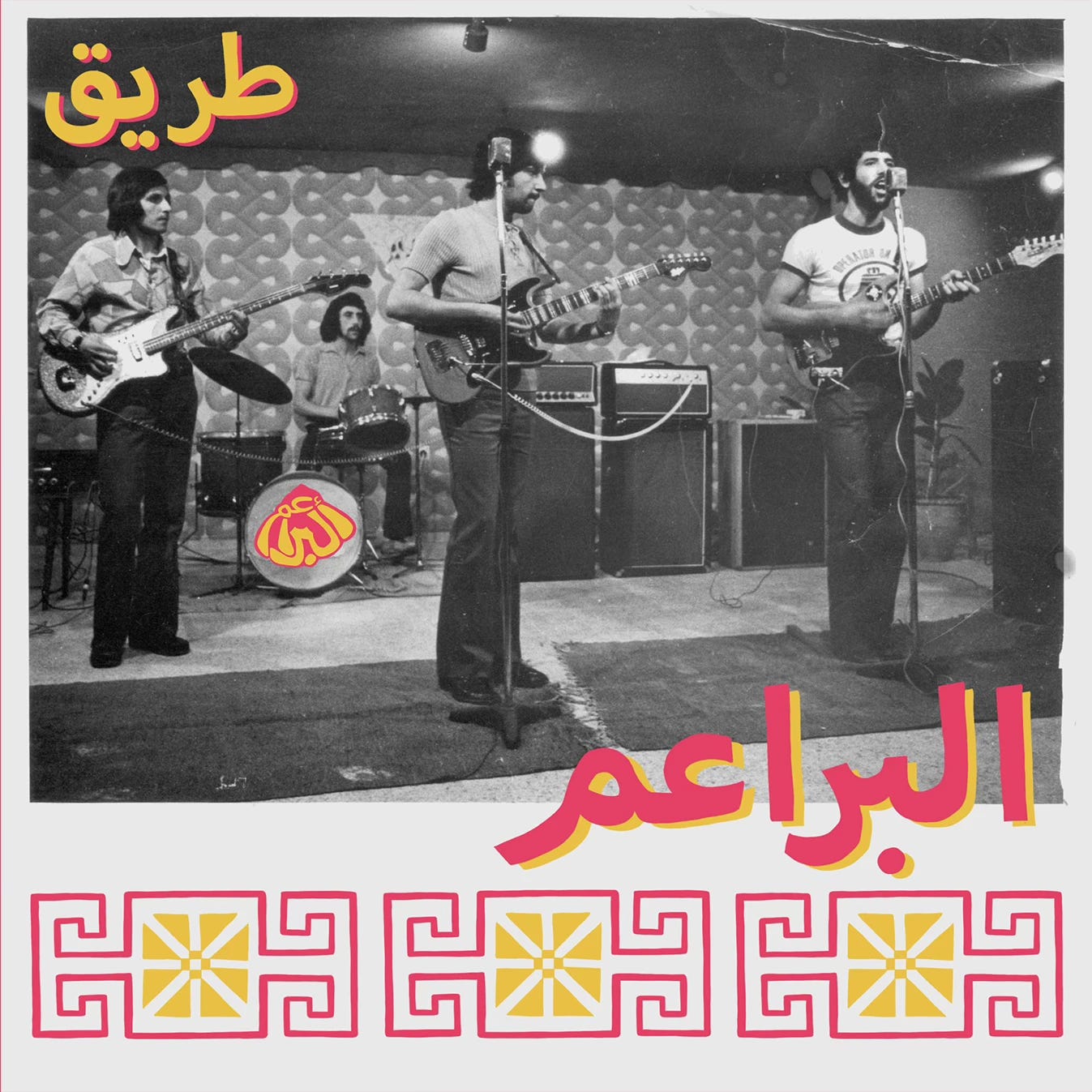

Al-Bara'em

In 1966, the first Palestinian rock band to write and perform original songs in Arabic was born. Al-Bara’em, meaning The Blooms in Arabic, consisted of Ibrahim Ashwari and his siblings, Alexandra, Emile, Samir and Samira as well as friends who would come and go from the lineup during their peak years. Like those before them, Al-Bara-em originally started covering English language rock songs from bands like The Beatles. Sometime in the early seventies they began touring with original Arabic music, with songs such as Tareeq, a poetic elegy based on a poem by Jibreel Al-Sheikh, to those who have lost their homes and their identity.

Do not ask me who I am

Suffice it that you are my comrade in my being lost

And I yours

And all I know is that

My sail took me blindfolded … blindfolded …. blindfolded

And so, I came down that road

Ibrahim Ashwari’s son Sama’an Ashwari attributes the shift towards Arabic-language songs as an emotional response to the conflicts of the late sixties and early seventies. The Six-Day War of 1967 and the Black September conflict of 1970 - which displaced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from the West Bank - meant that “dancing to The Monkees just wasn’t cutting it any more”. The need for Al-Bara’em to express themselves in a more authentic way felt more pronounced and significant.

Tha’er, is a call for solidarity across the world, insisting that no matter what life you lead, you’re never far from being a revolutionary. The band was radical in many ways, including the presence of female band members, making Al-Bara’em the first Palestinian rock band to feature women on stage.

لا تَقُل لي

Do not tell me

ليتني.

If only I were

بائع خبز في الجزائر

A bread seller in Algeria

لاغني

I would not sing

لاغنيها مع ثائر

I would not sing it with a revolutionary

The band would continue performing sold-out shows in Bethlehem and Jerusalem until around 1974, when four of the six siblings would be forced to emigrate away from their home. During that time, the band were one of the most famous acts in Palestine, once receiving a request from the UN to perform at their headquarters in Jerusalem. Like many artists from this period, studio recordings are very few and far between. Many Al-Bara’em tracks were never recorded, that is until recently.

Music writer and podcast host Sama’an Ashrawi discovered that his father Ibrahim and his uncles and aunties had been members of the pioneering band. This lead Sama’an on a journey from Houston, Texas all the way to the West Bank in 2019 on a research trip. Sama’an is now committed to releasing as much of their music as possible from the scarce archives that exist - mostly thanks to Sama’an’s uncle and band member, Emile - and the tracks listed above are a part of this effort.

You can learn more about Al-Bara’em below:

Vice: The Little-Known History of Palestine’s First Rock Band

Interview between journalist Iain Akerman and Sama’an Ashwari

Youtube playlist of currently released songs

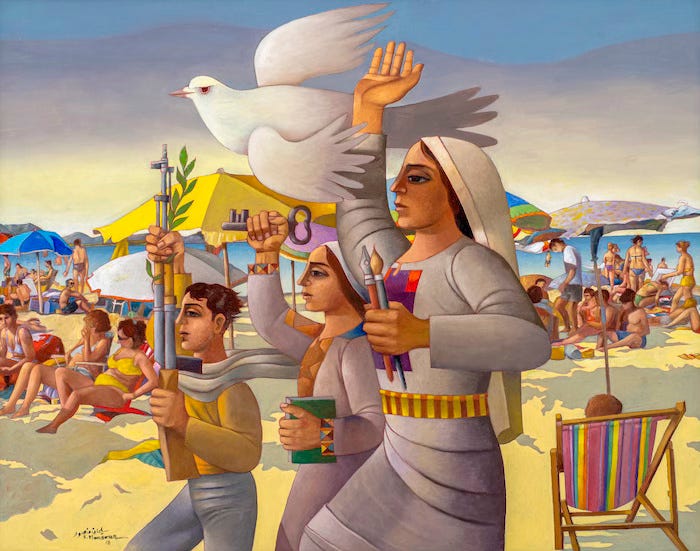

Sliman Mansour

Painter, sculptor, author, Sliman Mansour was born in Birzeit in 1947, a year prior to the formal ‘beginning’ of the Nakba in 1948 and the ensuing decimation of Palestine. The Nakba involved the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages and the expulsion of around 700,00 Palestinians from their homeland. The erasure of their “right to return”, meant that these citizens became permanent refugees, with no legal basis to contest. Many were “denationalised”, rendering their Palestinian nationality useless in the eyes of their oppressors, making it much more difficult to re-settle in a different part of Palestine or Israel.

Such is the context that artist Sliman Mansour grew up in. Perhaps “fortunate” in some way, Mansour’s right to remain in Israel stems from his “Jerusalem ID”, a form of ID given to those born in Jerusalem before 1967, when East Jerusalem was captured by Israel in the Six-Day War. It does not make the holder a citizen of Israel, but allows free passage within the state and internationally. Another way of managing the movement of Palestinians while denying them the broader benefits and significance of citizenship. After studying abstract expressionism at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, Mansour began to lean towards a more realist form of painting, depicting the everyday beauty of Palestinian life.

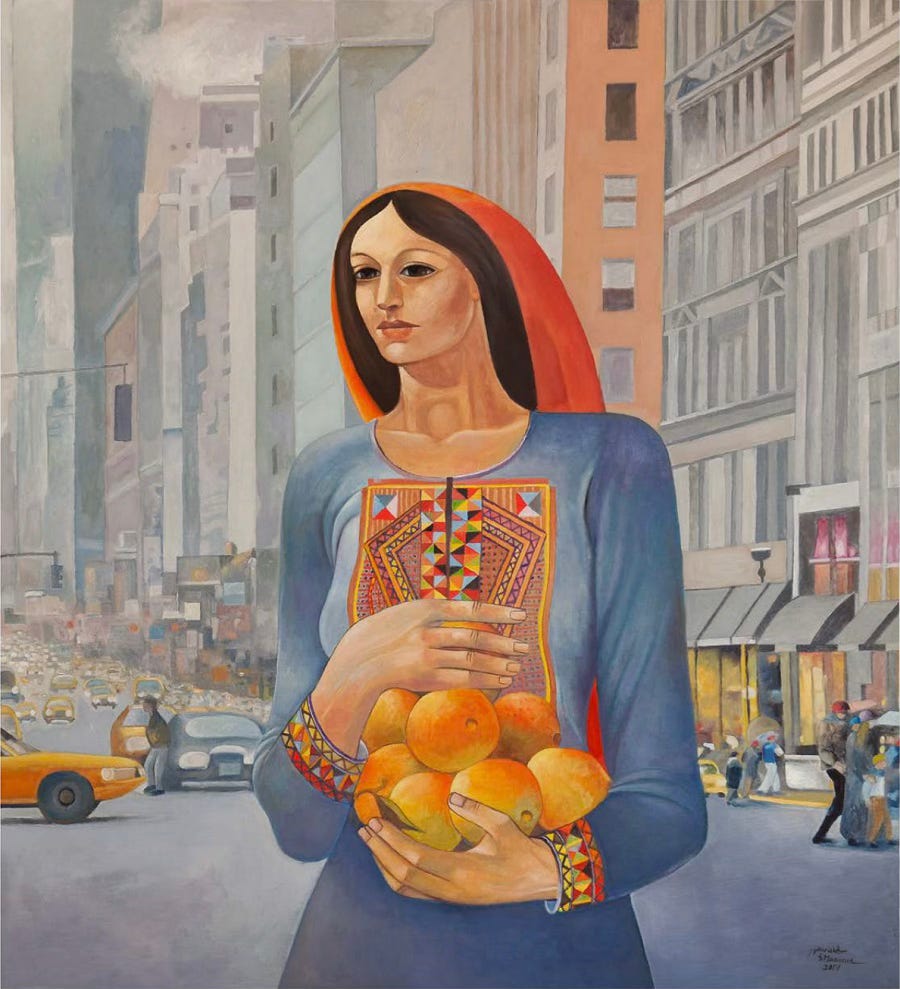

Via Instagram, Mansour expands upon The Immigrant (above) from 2017, a piece which contrasts a Western looking metropolis with the traditional head scarf and dress of the subject, the colours of the fabrics and fruits contrast with the greyish hues of the city. Mansour explains that The Immigrant “expresses the tremendous attachment to Palestine that Palestinians in exile hold dear in their hearts, which only grows the longer they reside in the diaspora”.

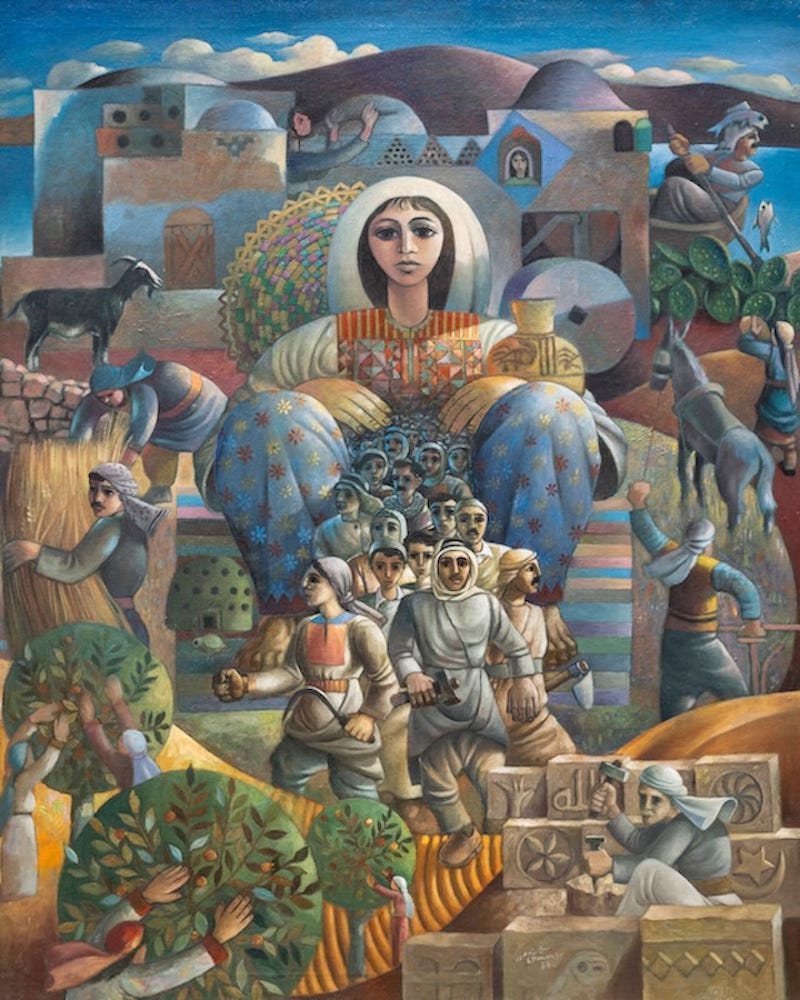

The Village Awakens from 1987, which Mansour recently reposted to honour the struggles of women who live under oppressive regimes, was produced the same year as the first Intifada, a Palestinian uprising against the Israeli occupation of Palestinian Territories. During this period of conflict, Mansour was a member of the New Visions collective, who organised a boycott of Israeli supplies, opting to use natural materials from Palestinian earth for their work, such as mud, henna and coffee. While Mansour is not actively a ‘political’ artist, it is hard not to be perceived as such when your very existence is a rebellious act against an oppressor.

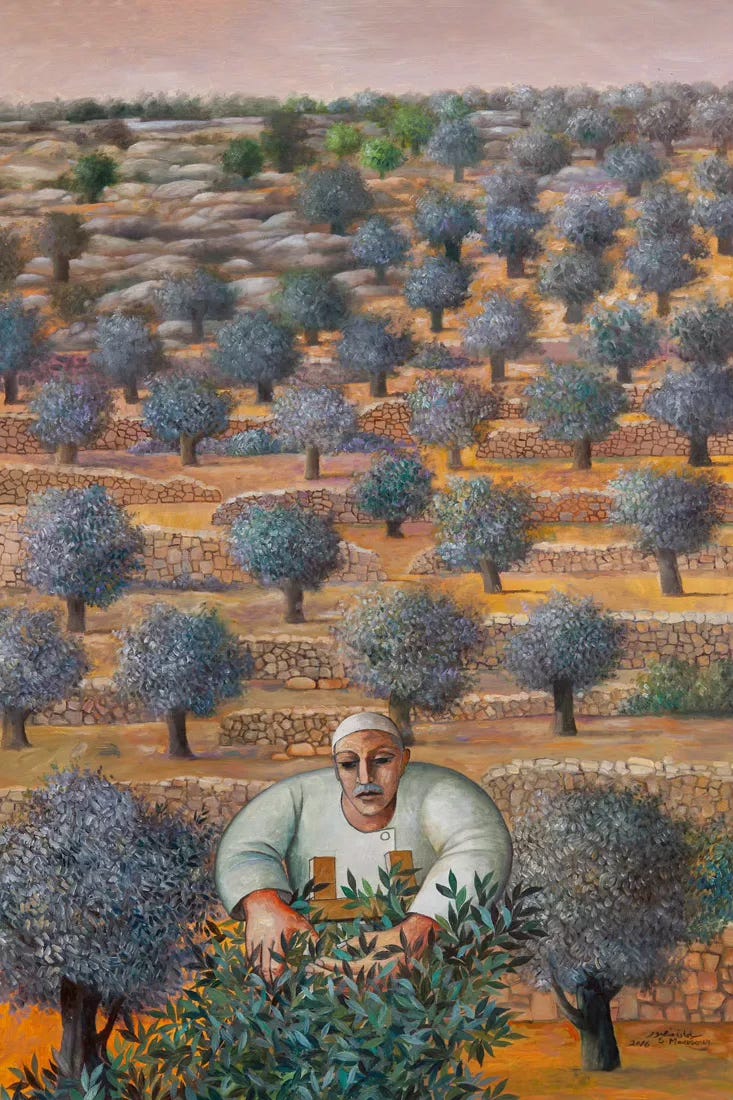

The olive tree features repeatedly in Mansour’s work, a symbol of peace and a Palestinian motif, of those who remain steadfast, rooted to their home. There is an essential, life-giving connection between Palestinians and the olive tree. As of 2021, between 80,000 and 100,000 families in the Palestinian territories relied on olives and their oil as primary or secondary sources of income.

Mansour remains in Palestine, living under occupation and painting a future that is beautiful and vibrant. Despite being an internationally recognised pioneer of Palestinian art, Mansour remains humble and grounded in his aims. “I hope, I hope. I would love to have my art make a change in the world about Palestinians, because they want to dehumanize the Palestinians. I hope and I think my art helps a little bit in changing that idea.”

For more on Sliman Mansour:

Karimeh Abbud

In 1913, Karimeh Abbud received a gift from her father As’ad that would change her life: a camera. This technical marvel had not been out of the gates long - the first Kodak camera ever sold arrived in 1888 - but Palestine was actually one of the first places outside of Central Europe to have access to photography. The first school of photography of its kind in Palestine was founded in Jerusalem circa 1860 by priest Yessai Garabedian.

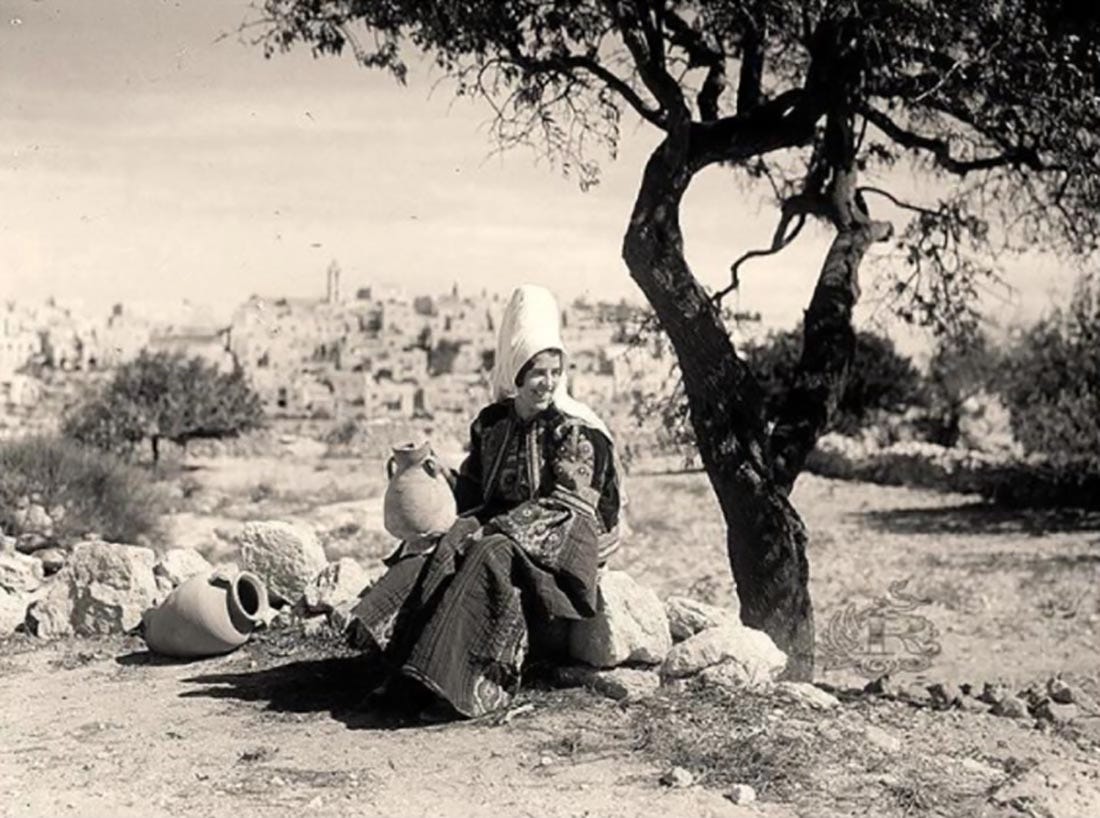

At just 17, Karimeh Abbud shot and developed pictures of family and friends, as well as sweeping landscapes of Bethlehem, Nazareth, Haifa, Tiberias and more. Abbud was well-travelled thanks to her education and steady work as a photographer. Self-branded as “The Lady Photographer”, Abbud was singular for the time, initially popular for weddings and other ceremonies as well as portraits. My favourite of her work are the portraits which incorporate beautiful landscapes, like the ones below.

Due to the archival scarcity of her work, dates for each photo are few and far between. After the Nakba, much less is known regarding Abbud and her career. Much of the archive surfaced in 2006, when an Israeli collector named Boki Boazz offered hundreds of photos from Abbud to the director of the Nazareth Archive Project, Ahmad Mrowat. Much of the detail on her life is also owed to Mrowat and this article. I love the photo above, the pottery that the woman holds resembles the clay-like textures of the buildings behind her and the tone of the photo, a symmetry of organic material and lived design.

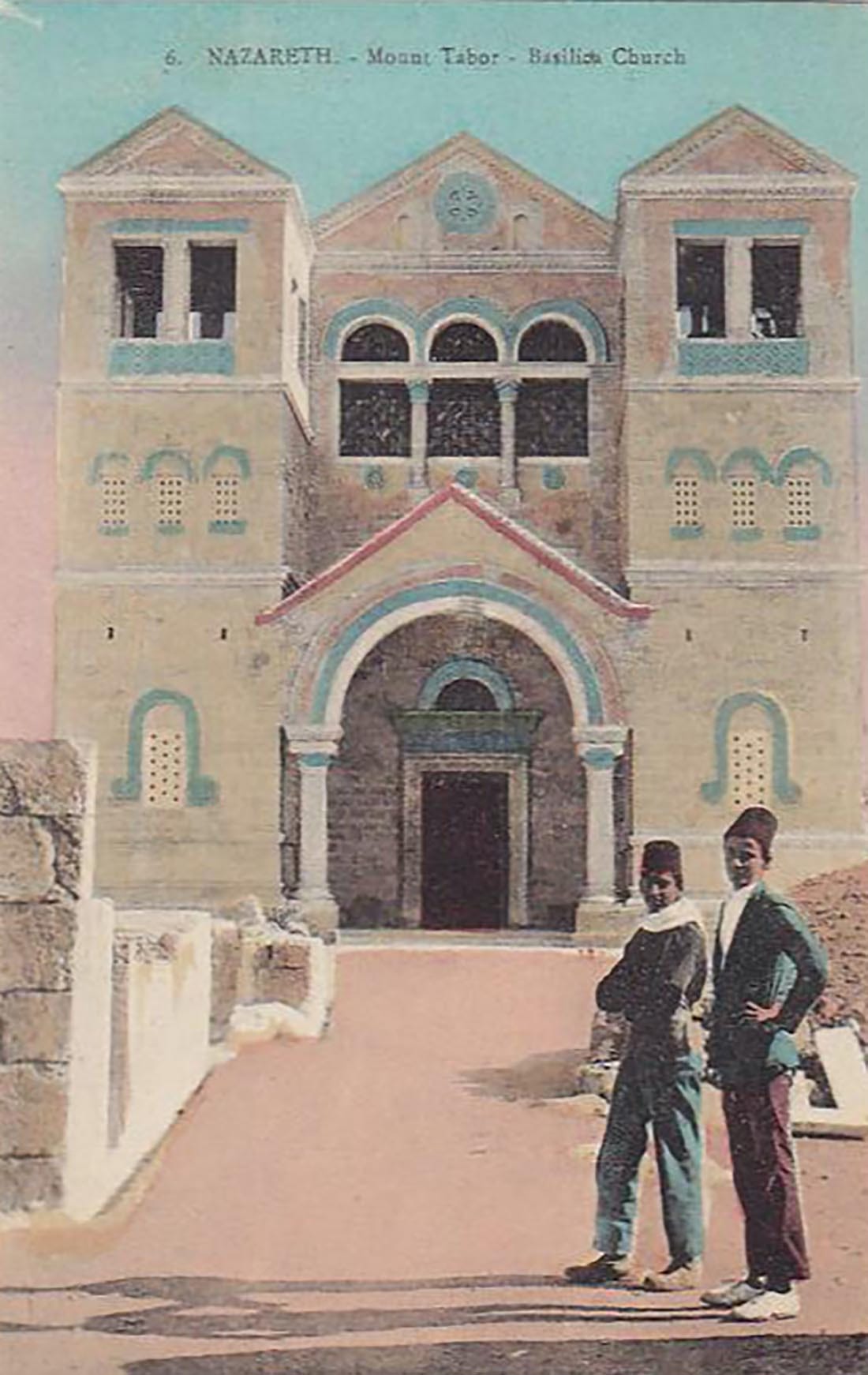

This photo taken at a church in Nazareth has lovely blue details in different shades, while perhaps having a personal connection with Karimeh’s father Asa’ad, a Protestant minister who preached in various settlements, including Nazareth.

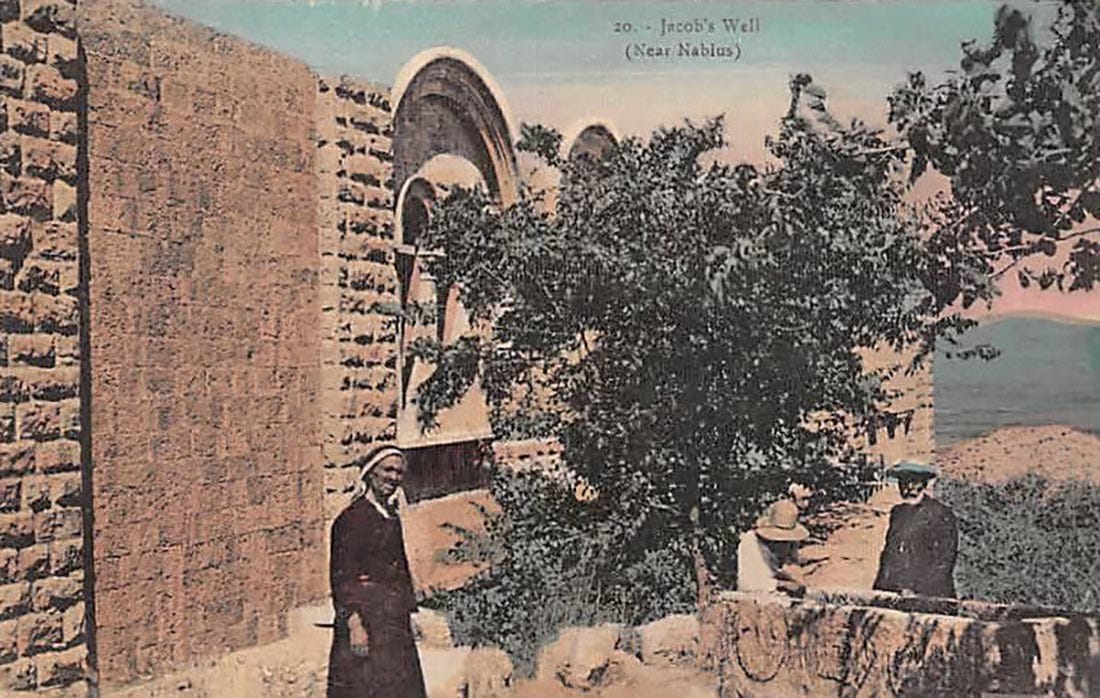

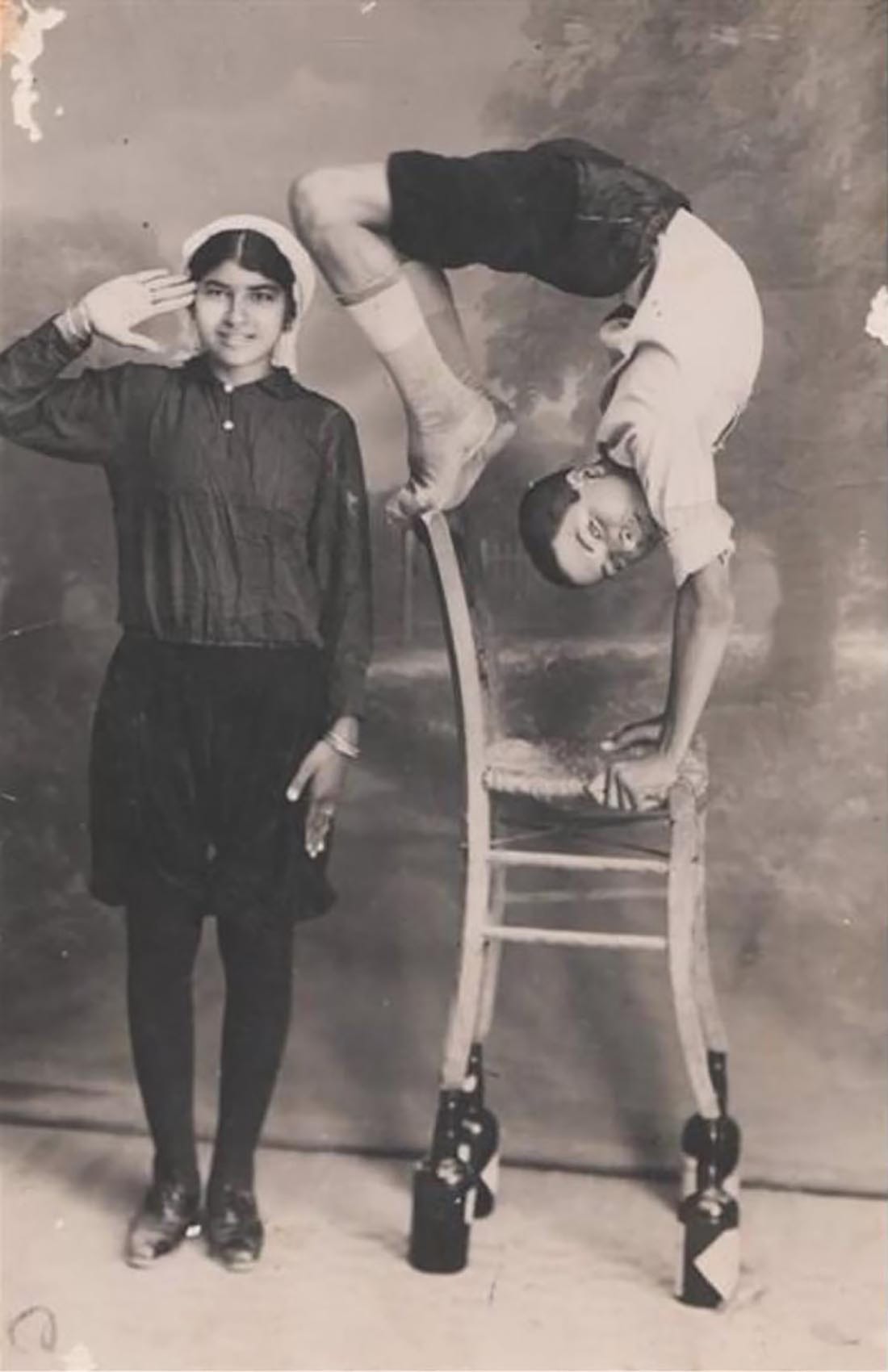

I leave you with this: two kids doing silly shit. Given how slow cameras were back then, it’s actually very impressive that he could do that for that long. I don’t know how you find out you can do that but it’s sick either way.

For more info on Karimeh Abbud:

“Who is Karimeh Abbud?” Afikra video

Substack is once again telling me to cease and desist with the long emails, so I’ll leave it there. I hope you enjoying this brief glimmer of Palestinian artistry from the last 100 years! I’ve included a few educational articles and resources if you’d like to learn more about the Palestinian struggle and take action yourself.

Decolonise Palestine reading list

Palestine Film Platform Archive

Until next time, be well.

Love,

Paulie x